Overview of theories of learning

APPENDICES: BASIC SUMMARIES OF LEARNING THEORIES

Before starting your assignment, you must read the basic summaries of key learning theory approaches provided here, to ensure that you understand them. If anything seems unclear to you, go back to a more detailed source and read it carefully, or seek assistance. You will not be able to write a good assignment if your understanding of the theories is partial, muddled, or inaccurate.

You should not reproduce, use as a reference, or directly quote from, any of the material in these summaries. Turnitin will flag any such use as potential plagiarism.

APPENDIX 1: ‘SCHEMA’

The concept of the Schema is key to a range of learning theories, and you will come across it regularly. It means an organised system of knowledge held in the mind, with facts and ideas linked together coherently. For example, in History, a schema for the First World War might include knowledge of when it began and ended, of its political causes and the main countries and figures involved, of conditions experienced by soldiers in the trenches, of the role of women both at home and on the front, of key battles, of protest movements and so on. It could also include cultural knowledge (e.g. war poetry and visual art of the period) and technological knowledge (e.g. the development of airborne warfare). Each new piece of information added to the schema helps to build up a clearer and more sophisticated understanding.

We can also see the building of a schema in terms of Bloom’s Taxonomy – it begins with

straightforward facts, but can develop into a more complex understanding of a domain of

knowledge, allowing for evaluation, exploration of contradictory ideas and so on.

NB – you will sometimes see schema pluralised as ‘schemas’ and sometimes as ‘schemata’. Either is fine to use – but you should pick one and be consistent. Throughout this document we have used ‘schemas’.

APPENDIX 2: MEMORY-BASED THEORIES OF LEARNING AND TEACHING

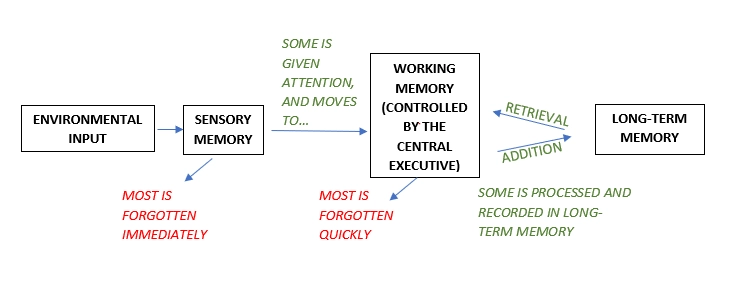

The ‘Working Memory Model’ proposed by Baddeley and Hitch (1974) is a general theory to explain the process of memory storage.

According to Baddeley and Hitch, (1974) memory has three stages – sensory memory, working memory, long term memory.

Sensory memory is the point of input. It holds information from our senses for less than a

second. Most is forgotten. Some is noticed (given attention) and moved to the working

memory, where the ‘central executive’ decides what to do with it.

Working memory lies between sensory memory and long-term memory. Here is where

information is processed. It is not just a temporary store, but a dynamic environment where

the brain’s ‘central executive’ interprets incoming information as well as related existing

memories. Working memory is where the central executive retrieves material from the long term memory store, then builds on or adapts it to incorporate new information.

Long-term memory is where information is stored more-or-less permanently. It has

unlimited capacity.

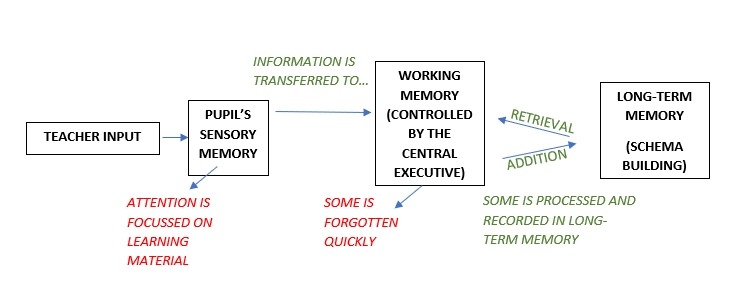

The general working memory model can be made more specific to teaching and learning:

John Sweller’s (1988) adaptation, ‘Cognitive Load Theory’, refines the Working memory Model to explain the role of memory in teaching and learning, and to argue for a particular set of approaches to classroom practice.

Baddeley and Hitch propose that there is a limit to how much information working memory can hold at one time. If we exceed those limits, the brain will struggle to deal with the input. Sweller (1988) builds on this idea to argue that in the classroom, a poorly designed teaching/learning activity can overwhelm a pupil’s working memory, and it will therefore produce ineffective learning.

His version of the Working Memory Model adds to the original in three principal ways:

- Focus on schema-building;

- A strong emphasis on the idea of working memory capacity, and on organising

information to avoid working memory overload; - The idea of different categories of ‘cognitive load’;

According to Sweller, the working memory’s function when learning is to help the long-term

memory build schemas. The concept of the schema comes from the work of Piaget; it refers to a knowledge structure in the human memory, which can be built up or adapted when further information is received. For example, a young child’s schema for rivers might begin with the ideas that they contain water, fish, and weeds, are much longer than they are wide, and flow through the landscape. Later, the child could add further knowledge to the schema: for example, that rivers always flow downhill, will usually combine with other rivers to become larger, and eventually reach the sea. If more learning is added effectively, the schema becomes increasingly complex and detailed.

The three types of cognitive load Sweller proposes are:

- Intrinsic Load – the material which, when learned, will be integrated into the schema for the topic or concept being studied.

- Extraneous Load – information the pupil needs to remember in order to engage in the learning activity. Extraneous load takes up memory but does not contribute to building the schema.

- Germane Load – memory used to combine new material with the existing schema.

He suggests intrinsic load cannot be changed or reduced – but teachers can limit the amount of intrinsic load pupils need to deal with at any time. They can also organise intrinsic load logically, so that it builds up effectively and develops the schema over time.

The most effective learning, Sweller argues, can only occur when extraneous load is minimised. Some activities might be engaging or enjoyable, but because they occupy significant cognitive load they can reduce or even replace the learning they are meant to facilitate. Sweller contends that teachers should always look for efficient methods.

Germane load is not directly controllable in Sweller’s model. However, he suggests germane load is optimised when teachers organise intrinsic load carefully and minimise extraneous load.

Sweller’s arguments are based on ideas of efficiency in learning. He does not seem to give much weight either to variations in the material being taught or to the nature and context of the learners. While CLT does not promote a particular teaching method, its emphasis on control, structure and organisation of material will typically point to teacher-centred pedagogies.

Key points in cognitive load theory

- The stages of memory processing

- The limited capacity of working memory

- The idea of schema-building

- Sweller’s three types of cognitive load

- The need to minimise extraneous load and organise intrinsic load

Another popular model for teaching and learning that builds on Baddeley and Hitch’s work is Rosenshine’s ‘Principles of Instruction’. While Rosenshine does not break down memory in the same way as Sweller, and he is more committed to a specific teaching method, his proposals for organising material are similar. (Rosenshine and Stevens, 1986 – see especially the remarks about applicability of the procedures on p.3).

References

NB – in this document we have included URLs of book extracts and journal articles for your convenience. If you name any of these texts in your assignment reference lists, the bibliographic citation is enough. URLs are only required where there is no bibliographical reference (e.g. for YouTube videos, online news articles, blog entries etc.

Baddeley, A. and Hitch, G. (1974). ‘Working Memory’. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 8: 47- 89. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0079742108604521#aep-abstract-id6

Rosenshine, B and Stevens, R. (1986). ‘Teaching Functions.’ Handbook of Research on Teaching. 376-391.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230853009_Teaching_Functions/link/564a1ca208ae295f644fb513/download

Sweller, J. (1988), Cognitive Load During Problem Solving: Effects on Learning. Cognitive Science, 12:257-289 https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog1202_4

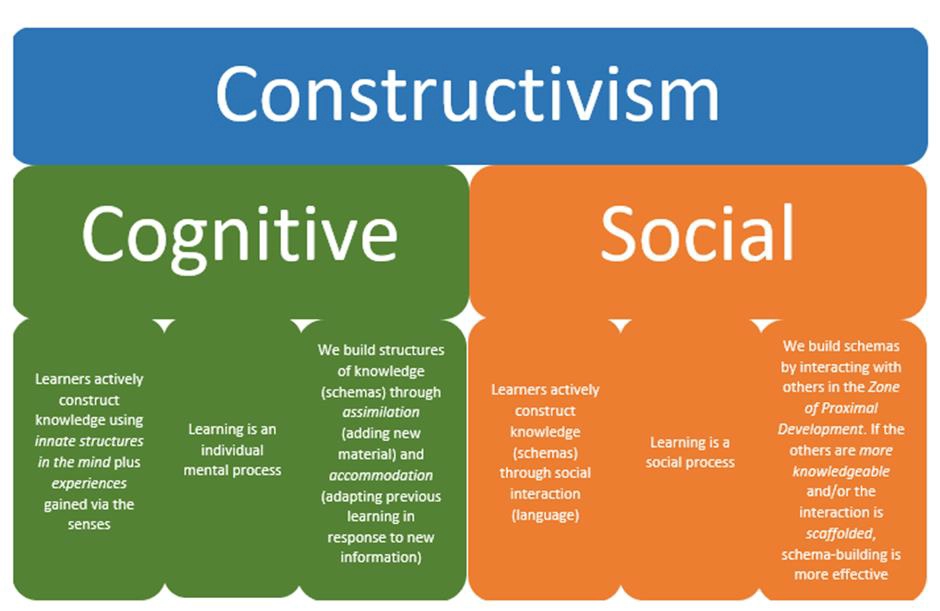

APPENDIX 3: CONSTRUCTIVISM

Cognitive Constructivism (Piaget)

Piaget’s focus was on the development of learning abilities during a typical childhood and

adolescence, which he divided into four main stages. For the purposes of secondary teachers, the latter two stages are most important. Children leaving primary school at 11 are still in the ‘concrete operational stage (roughly ages 7-12): centred on their own experiences, they can apply logic but will struggle with anything abstract. From around Year 9 in the UK system, they will be in the ‘formal operational stage’ (adolescence) in which they develop the ability to think more abstractly without referring to concrete objects, empathise with others, and explore differing points of view. This stage leads to intellectual and emotional maturity

Process through these stages is partly through biological development and maturation of the brain. However, in Piaget’s view the process of learning is one of active construction by the learner. He proposes that learning has two characteristics – we assimilate new information (add it to an existing schema) or accommodate it (revise an existing schema so it will fit in). This, he argues, is always achieved actively by the learner, who encounters challenges to an existing schema and must find away of integrating the material.

Piaget himself did not propose any approach to teaching and learning. However, after ‘progressive’ educationalists in the late 1950s rediscovered his theories, they became highly influential on classroom practice. Constructivism as an educational approach is often seen as a rejection of the traditional ‘teacher-centred’ view of the child as an empty vessel who can simply be filled with information by direct instruction.

Implications of Constructivism for teaching and learning

Following Piaget’s argument that learners do not passively internalise information – but rather they actively construct knowledge for themselves, constructivism says it is not enough for teachers to material to pupils with the idea that they will add it to their memory store. Instead, we need to design classroom experiences: ways for pupils to engage meaningfully with the material – such as problem-solving, debate or creative activity.

Social Constructivism (Vygotsky)

An important refinement of Piaget’s ideas was proposed by Lev Vygotsky (1978), who argued that human learning cannot be explained simply as a process of committing material to memory within the individual mind.

While Piaget saw learning as largely internal to the individual, Vygotsky emphasised the role of the social process. Interaction with other human beings, in his view, is the essential component

He argued that unlike other animals, humans understand the world in terms of concepts that can only be understood through language. Consequently, he said, we can only learn through communication. The more effective the communication, he concluded, the more effective the learning.

He divided development into:

- The level of actual development (what can the student do now?)

- The zone of proximal development (what can the student do with guidance and support?)

For Vygotsky, learning meant moving the level of actual development into the zone of proximal development, so that what a child can do with help today becomes what they can do independently tomorrow.

This is best achieved, in his view, by interaction with a more knowledgeable other. The ‘more knowledgeable other’ may be the teacher, or a more advanced pupil, or (for example) a pre-recorded video guide.

Later followers of Vygotsky introduced the term ‘scaffolding’. (Wood, et al, 1976). In the context of post-Vygotskian theory, scaffolding means providing a structured process of guidance, carefully designed to provide temporary support while the student achieves independence and confident understanding.

You may have heard the term ‘scaffolding’ used to describe memory techniques (such as acronyms) and/or mechanical processes a pupil can follow to complete a task, such as ‘BIDMAS’ or ‘PEE Paragraphs’. These would not be considered scaffolding in social constructivism.

For Wood et al (1976) the key elements to effective scaffolding all involve social interaction with the learner:

- Motivation – keeping the learner interested and preventing frustration

- Simplification — making the task accessible to the learner’s current level of understanding

- Focus – drawing the learner’s attention to the elements of the task that will lead to

completion - Demonstration – showing the learner the task being completed

Poor scaffolding simply helps the student complete a task; it does not facilitate learning.

Consequently, it often ends up being left permanently in place. Good scaffolding makes difficult material more accessible and speeds up the learner’s progress into the ZPD. Most importantly, it can be ‘faded’ as the student takes independent control over knowledge and skills.

Key points in social constructivism

- Vygotsky’s idea that social interaction through language is the key process in learning

- The Level of Actual Development and the Zone of Proximal Development

- The role of the ‘more knowledgeable other’

- The concept of ‘scaffolding’

NB – when writing about Vygotsky, remember that he died in 1934. His work only became

important in the West many years later, following publication of a translation of Thinking and Speech in 1962. Consequently, references to his work will usually be dated long after they were written and published in Russian. Mind in Society, cited in the references here, is a 1978 collection of his essays translated into English.

The two main traditions in Constructivism – summary

References

Piaget, J. (1951) Play, Dreams and Imitation in Childhood, Trans C Gattegno and F.M. Hodgson Routledge, London.

(Full text available as an eBook via University Library https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/leicester/detail.action?docID=1273074)

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

(Full text available as an eBook via University Library https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/leicester/detail.action?docID=3301299)

Wood, D., Bruner, J., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Child Psychiatry, 17, 89−100. https://acamh.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x

APPENDIX 4: HUMANISM

Of the three approaches summarised here, Humanism is the only one that directly considers how the process of learning may be dependent on a learner’s socio-economic realities and emotional experiences.

Humanist approaches to education emphasise the needs of the individual pupil; they suggest that learners’ agency and motivation are key factors in successful learning. In humanism, the cognitive elements of learning (understanding and remembering) are seen as inseparable from the affective elements (feelings and motivation). Consequently, humanist thinking encourages teaching ‘the whole child’, rather than focussing narrowly on one aspect, such as memory.

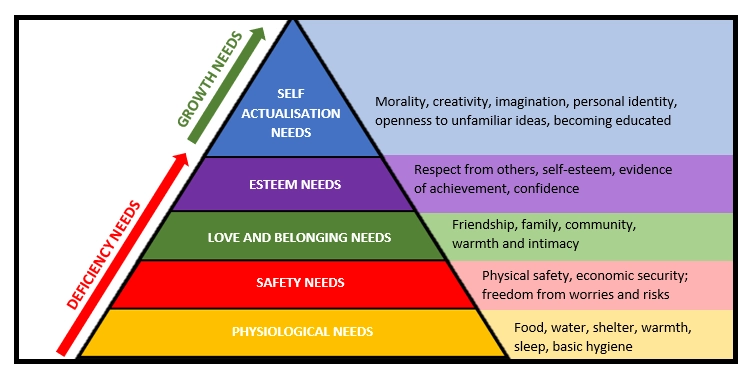

Humanism began as a reaction against the behaviourist argument (e.g. of B.F. Skinner) that human beings are motivated only by their responses to reward or punishment. Abraham Maslow, usually considered the founder of the humanist approach, contended that human beings are complex moral agents, who are naturally biased towards good choices. However, their environment does not always make such choices viable or attractive.

Maslow suggests we all have a ‘hierarchy of needs’, beginning with physiological basics vital to survival, and building towards more abstract factors that allow us to reach our full potential as human beings. He calls the latter ‘self-actualisation’. We may never fully achieve self-actualisation, but all humans will strive towards it, if the conditions are right.

This is not a linear progression. Maslow does not argue that we must entirely satisfy each level before moving on to the next. At any time during a person’s life, a person may experience a mixture of met and unmet needs from different levels. For example, one may have friends even if food is in short supply. However, an unmet need for food will always be a higher priority than the need for friendship, and so it will occupy more of our attention. Maslow suggested that the first four levels of his hierarchy can be characterised as ‘deficiency needs’ and the top level as ‘growth needs’. If the deficiency needs are all met, he argued, most people will then devote their attention to their growth needs.

Education is largely concerned with self-actualisation – a focus on the future and on personal development. But, humanism argues, a pupil can only properly attend to those needs if they are not hungry, sleep-deprived, economically insecure, isolated, and lacking self-esteem. The humanist model of education suggests learning will not succeed if it focusses only on its obvious purpose (self-actualisation) and ignores pupils’ deficiency needs. Consequently, the school’s pastoral role is integrated with the educational role.

Humanism also has implications for individual teachers’ lessons. For example, in terms of safety needs, classrooms should be emotionally secure, supportive environments where pupils feel free to express themselves, explore ideas, and sometimes make mistakes. As well as shaping approaches to behaviour management, therefore, a humanist approach will define how teachers ask questions, organise tasks and provide feedback.

The humanistic model assumes that all pupils want to self-actualise, once enough of their deficiency needs are met. Consequently, it argues for a classroom where the focus is on motivation and engagement. In a humanist classroom, pupils are encouraged to have a degree of autonomy and control over their own learning – to make choices about the work they do and how they do it. They are given space and time to follow their interests. A focus on grades, rote-learning and testing is discouraged. There is a preference for self-evaluation. A recent development in the humanist tradition of self-actualisation is Carol Dweck’s idea of the ‘growth mindset’, which proposes that pupils learn best when taught ‘to love challenges, be intrigued by mistakes, enjoy effort, and keep on learning.’ (2006) An overtly politicized version of the humanist model is promoted by Paulo Freire in his Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970).

Key points in humanist education theory

- The idea of teaching the whole child

- The hierarchy of needs

- Deficiency needs and growth needs

- The focus on motivation and engagement

- Emphasis on pupils being involved in shaping their own learning

Freire, P. (1972) Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Trans. M.B. Ramos, Penguin, Harmondsworth

Yeager, D.S. and Dweck C.S. (2020) ‘What Can Be Learned From Growth Mindset Controversies?’ American Psychologist 75(9) 1269-1284.

What Can Be Learned from Growth Mindset Controversies? – PMC (nih.gov)

Maslow A. (1943) ‘A Theory of Human Motivation’ Psychological Review 50(4) 370-376.